Today, Friday 8 March, is International Women’s Day 2019 and the theme is #BalanceforBetter. It is fitting then that today’s post explores the story of a pioneering artist and archaeologist and aims to restore some of the balance in the history books… #IWD2019

***

It was a cold Thursday morning, here in the conference room at the museum, that I fell in love with Adela Breton. It was a Museums North West workshop, and our Curator of Living Cultures, Stephen Welsh brought her lo life with stories of pioneering adventure. By the morning coffee break I needed to know everything about her life, travels and impact on Mesoamerican archaeology …

This also got me thinking… I have long been interested in telling the stories of the people of Manchester Museum, and and especially re-gendering the narratives that surround our objects and collection, so why had I not already heard of her? When did she fall out of the history books?

Adela Catherine Breton (1849-1923)

Adela Breton was a strong, determined, stubborn, independent, and seemingly at times outspoken woman. She resisted the stereotypes of her generation, and forged her own path through life, and through the deserts and jungles of Mexico and South America.

#LifeGoals

Adela Breton photographed here with her mother and father, and his twin brother. (Ea 11509 Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. Source: artuk.org).

Adela Breton photographed here with her mother and father, and his twin brother. (Ea 11509 Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. Source: artuk.org).

Born on 31st December 1849, to mother Elizabeth and father William Breton, and it was perhaps from her father that Adela inherited the wanderlust, which was to become one of her defining characteristics. William Breton’s career with the Royal Navy took him all over the world, and he would bring back objects and curiosities, which gave Adela her first glimpse into the fascinating world of archaeology.

“I may tell you that I have been travelling & studying in Mexico for the last 12 years, & all my life have been learning archaeology as my Father was much interested in it.”

– Adela Breton to Richard Quick (Curator of Bristol Museum and Art Gallery from 1904-1921), 30 January 1905 (Bristol City Museum)

As was the way for Victorian ladies of Adela’s time, art and drawing will have formed an important part of her education, being taught by drawing masters. And by then it was not unheard of that women could earn money through their art and writing – nevertheless, Adela pushed this mould to breaking point!

Traveller, Artist, Archaeologist

The fulfilment of her childhood dream of travelling came in the early 1890s, following the death of her father in 1887 (her mother had died in 1874). It was probably 1894 when she first journeyed to Mexico, where she travelled and sketched extensively. This was to shape her artistic and archaeological career.

Watercolour by Adela Breton of the ‘Pyramid of the Niches’ at El Tajin. (Ea 8144, Cat. No. 40 – Bristol Museum and Art Gallery)

Watercolour by Adela Breton of the ‘Pyramid of the Niches’ at El Tajin. (Ea 8144, Cat. No. 40 – Bristol Museum and Art Gallery)

Adela was a fine artist, even Edward Thompson, the United States Consul to the Yucatan, with whom she had a turbulent relationship, noted her skills. Having accused her of ‘meddling’ at Chichen Itza, he wrote to Frederic Putnam, Curator of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University:

“To my horror I found out the day I left Chichen that she proposes to return to Chichen shortly for another period of time. She certainly is an artist as regards landscapes at least and she has made one painting in the intervals of her work for Maudslay that is really very nice. She brought out the artistic points of the “Nunnery” in a wonderful manner.”

Thompson to Putnam, 5 April 1900 (Harvard University Archives)

Adela Breton’s watercolour of “The Nunnery”, to which Thompson referred in his exchange with Putnam. (Ea 8429, Cat. No. 2 – Bristol Museum and Art Gallery)

Adela Breton’s watercolour of “The Nunnery”, to which Thompson referred in his exchange with Putnam. (Ea 8429, Cat. No. 2 – Bristol Museum and Art Gallery)

And again on 29 July 1900, Thompson wrote to Putnam:

“She has a very peculiar character but I think that she is one of those persons that improves as one knows them better. She most certainly is a true artist.”

(Harvard University Archives)

Adela was less concerned with aesthetics than with accuracy. She would practice and paint the same architectural element over and over again, correcting each carefully. As she wrote to Alfred Tozzer, Instructor in central American Archaeology at Harvard University, on 22 August, 1921, “In that way one trains eye and hand.”

Adela Breton’s watercolour copy of panels 6 to 11 stucco facade of the temple on the pyramid at Acanceh. (Ea 8186a Cat. No. 33 Bristol Museum and Art gallery – Image from artfund.org)

Adela Breton’s watercolour copy of panels 6 to 11 stucco facade of the temple on the pyramid at Acanceh. (Ea 8186a Cat. No. 33 Bristol Museum and Art gallery – Image from artfund.org)

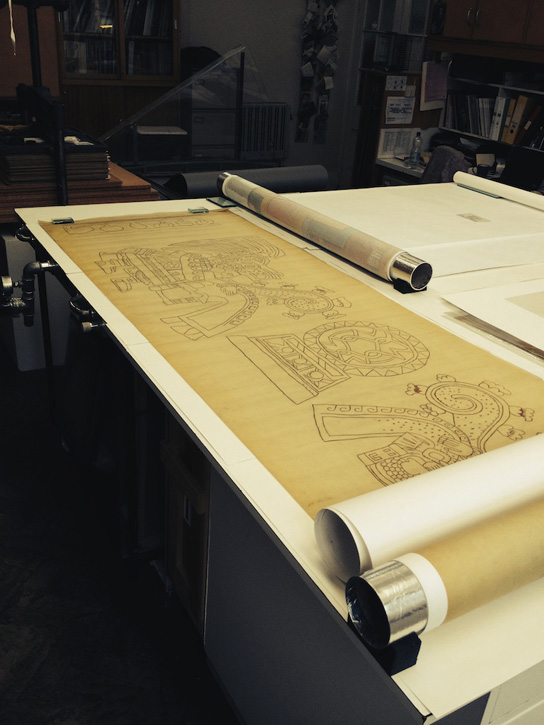

To make life-sized images was, quite literally, a HUGE task, and even at one point enlisted the help of her brother, an expert draughtsman. And the more she worked, the more popular her work became, to the extent that the commissions that she was taking began to interfere with her own work and research…

And by this point, that she had moved beyond simply travelling and sketching, but was making an archaeological impact. The more she became involved in recording the archaeology, the more she cited an need for an intimate knowledge of the languages.

#TrowelBlazer

The Who’s Who of Mesoamerican Archaeology

Adela is described in the 1911 census as ‘Archaeological Artist’. She started out as a landscape painter and as a copyist, but becoming more involved and invested in Mesoamerican archaeology, her later publication shows how much broader and professional her involvement in the field had become. In her day, she would have been ranked among the ‘who’s who’ of Mesoamerican archaeology, corresponding with and publishing alongside the likes of Tozzer, Putnam, Bowditch, Zeila Nuttall, Maudslay and Seler – a distinguished, international group of scholars!

#SquadGoals

So, what happened? Why did Adela Breton all but disappeared from the history books of Mayan archaeology?

Perhaps one of the reasons is that she didn’t quite fit. Her work was archaeological, centred around the meticulous water-coloured reproduction of the intricate carvings and monumental architecture, but by the 1960s, archaeology had entered a scientific era, that was distancing itself from fine art, and sweeping landscapes. Further, the objects that Adela had collected for the most part did not come from archaeological excavations, and the processual march of the twentieth century was now privileging context and provenance. This decline in value left the Breton archive under a shroud of obscurity for nearly half a century.

Legacy

Today, there is a renewed interest in work like Breton’s, both from a historiographical perspective, but also in the value of the details of her paintings showing decoration, images and paintwork that has since been damaged beyond repair.

From 1899 Breton loaned material to the newly established Bristol Art Gallery & Museum of Antiquities. In her letters, she urged the Director to establish it as a centre for Central American study in Britain and, in 1923, bequeathed her collection to the Museum.

Bristol Museum have been working with Art UK Digitisation Services on a project to photograph the archive with the help of the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation. The first phase of which has included, creating high-resolution images of the tracings of the frescos at Chichén Itzá. (Source: artuk.org).

Bristol Museum have been working with Art UK Digitisation Services on a project to photograph the archive with the help of the Esmee Fairbairn Foundation. The first phase of which has included, creating high-resolution images of the tracings of the frescos at Chichén Itzá. (Source: artuk.org).

Adela’s Collection in Manchester

On 14 December 1899 Manchester Museum received a considerable number of her collection of obsidian implements, and in 1923, at her bequest we received several figurines, depicting humans and reptiles. And this remains as our tangible connection to Adela Breton, her life and her legacy.

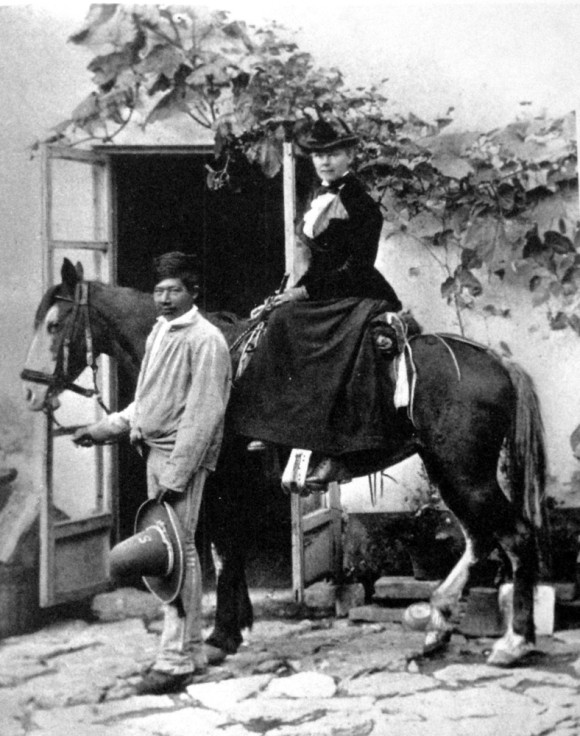

Adela comes across as both loyal and compassionate, she wrote of her sadness at the death of her Mexican guide, Pablo Solorio, who would collect artefacts for her, and through the correspondence for the rest of her lifetime, this loss stayed with her. She also cared deeply for her family and broke from her life of travel to be with her brother following the death of both his wife, and then his daughter.

Adela herself did not marry, but she did not conform to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century idea of a spinster! Her independence and her pioneering traveller’s spirit belongs to a far more modern era.

One Thursday morning, separated by a century and thousands of miles, I fell in love with Adela Breton. Her letters and artwork, give us a glimpse into a fiery personality inside a frail body, they tell a story of her determined work ethic and her passion for ancient stone, and across time and space she continues to inspire.

#IWD2019

Michelle Scott

Find out more:

trowelblazers.com – Adela Breton: A Career in Ruins

trowelblazers.com – Adela Breton: The Eccentric Miss Breton

artuk.org – Digitisation of the Adela Breton Collection at Bristol

artfund.org – Adela Breton: Ancient Mexico in Colour Exhibition

bristolmuseums.org.uk – Adela Breton

Lake Chapala Artists: Adela Breton

Sparrow-Niang, J. 2017. The Remarkable Miss Breton: Artist, Archaeologist, Traveller

Breton, A. 1902. Some Obsidian Workings in Mexico

bristolmuseums.org.uk – Adela Breton: Your last chance to see her work

Title image: Adela Breton, with Pablo Solorio, her guide in Mexico.

One thought on “Adela Breton”